Insights

The root cause of electricity price rises

28/11/2022

Electricity prices are rising in Australia, with predictions that retail prices will rise by more than 50 per cent1 over the next two years. Underlying this rise is the significant increase in coal and gas prices which are input costs to generating electricity. Some see the solution to this problem as capping gas prices. But the rise in gas prices is only a symptom. The root cause of the problem is the global demand for coal and the rapid rise in coal prices. Australian coal-fired generators have been increasingly purchasing coal linked to international prices, especially in New South Wales. So any efforts to intervene to reduce electricity prices should focus on coal prices as inputs to power generation.

The current state of the international coal market

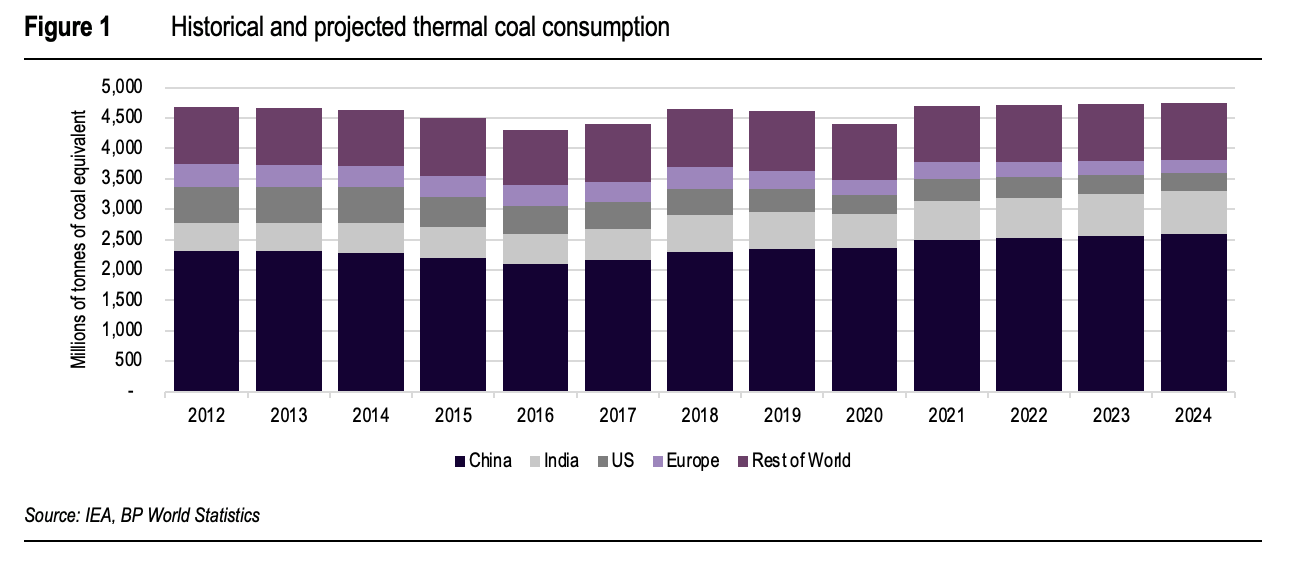

Global thermal coal consumption declined between 2012 and 2016 but began to increase again in 2017 - as shown in Figure 1. Apart from a dip during 2020, caused by the COVID-induced reduction in global economic activity, global coal consumption has been rising since 2017, driven by increased demand from China and India. In 2021, global consumption exceeded the previous peak in 2012. Global demand is projected to increase by around 1 per cent per annum to 2024.

Global coal reserves are currently at more than 100 years of current annual consumption levels. However, developing and exploiting new coal mines is becoming increasingly complex, especially in the developed world. Therefore, coal supply has tightened in recent years, and the global coal market has less capacity to respond to significant increases in demand.

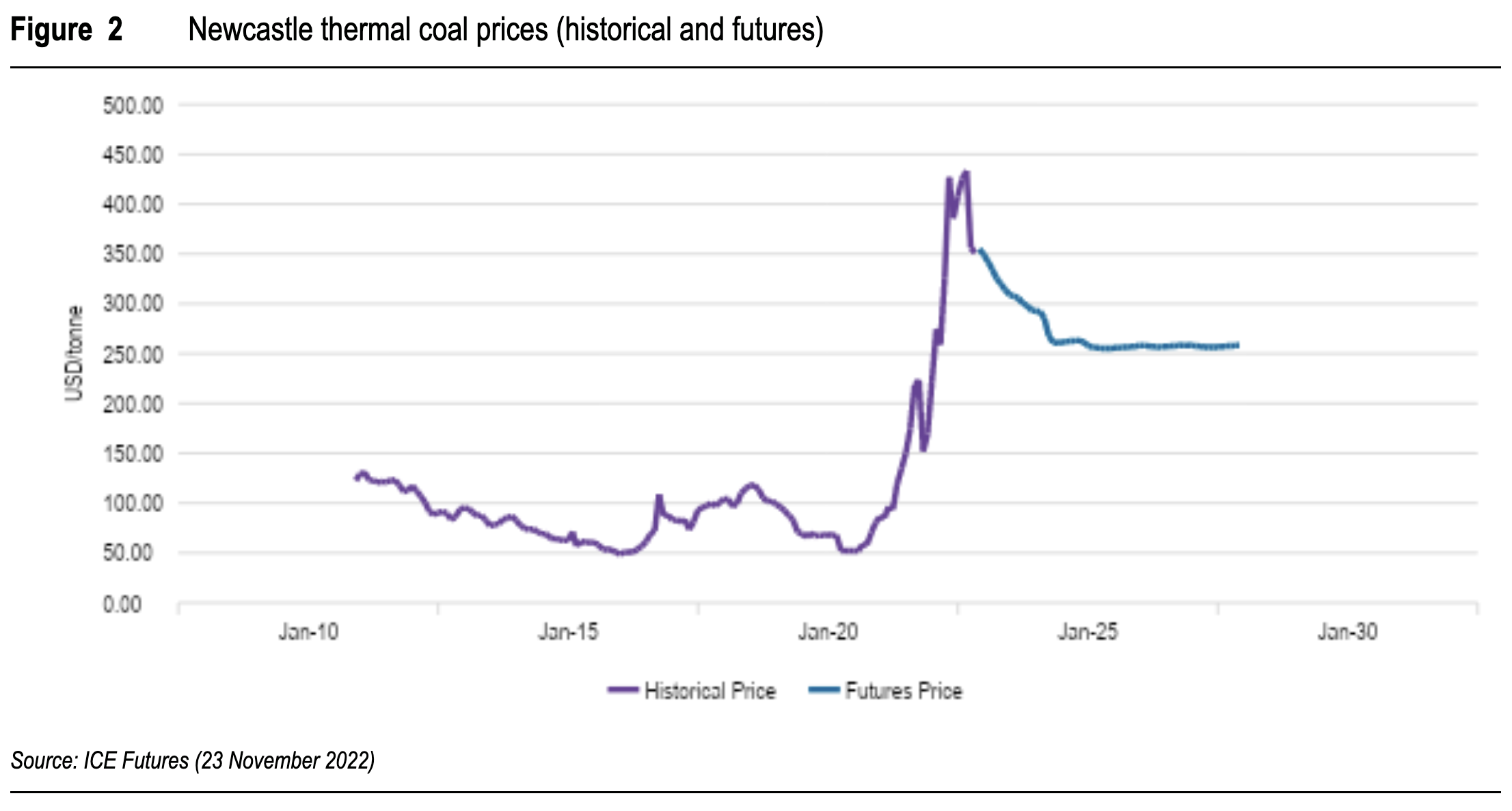

As shown in Figure 2, the Newcastle thermal coal price mainly traded from USD 50 to USD 100/tonne from 2010 to 2020. However, as demand rose throughout 2021 in response to the global economic recovery from the COVID pandemic, prices also rose as a result. Prices peaked at USD 223/tonne in October and remained above USD 150/tonne for the remainder of 2021. The commencement of hostilities in Ukraine in February 2022 turbocharged the international coal price to above USD 400/tonne, with current spot prices continuing at around USD 350/tonne.

Coal prices are a key influence on electricity prices

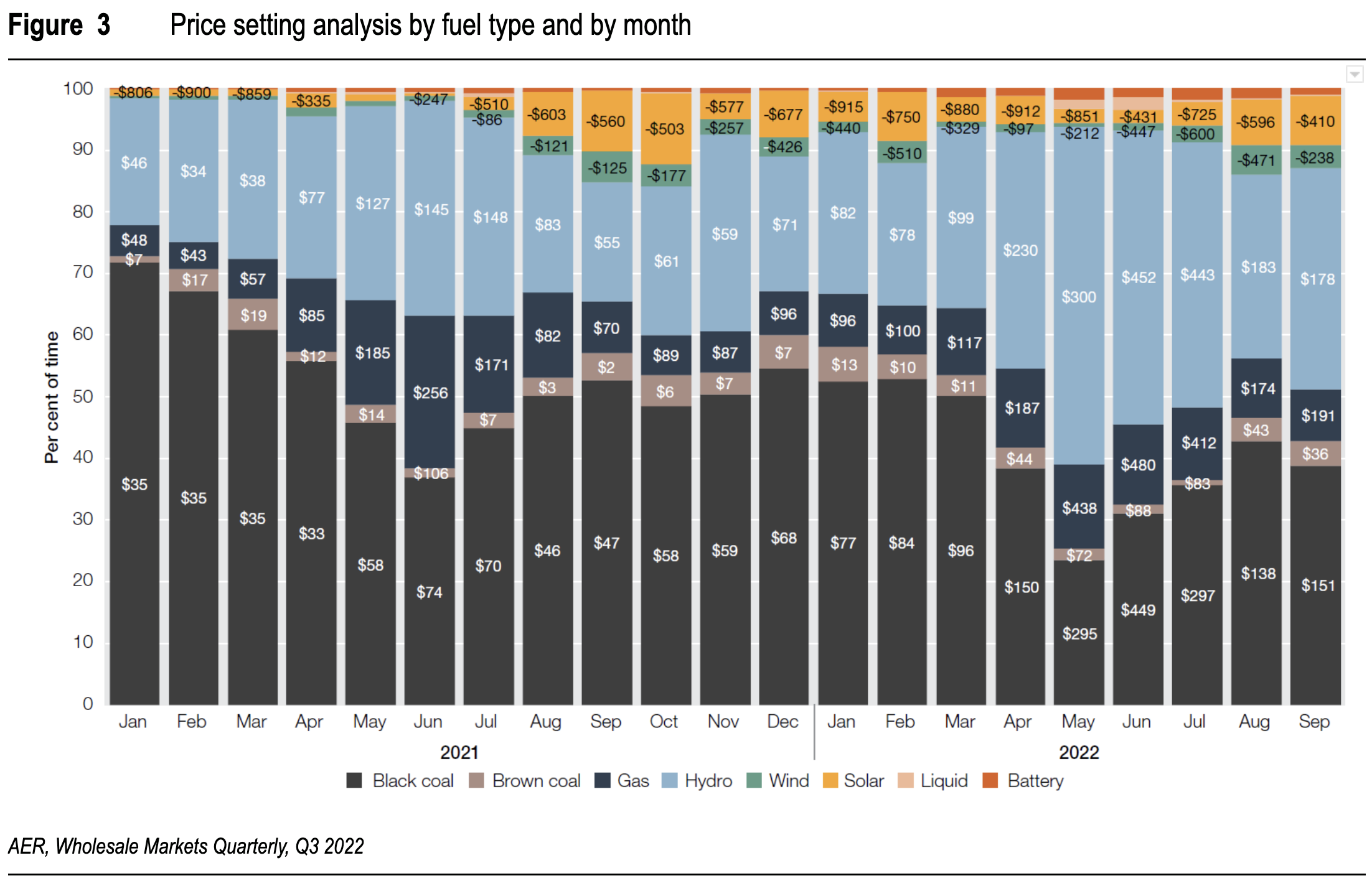

Gas generation typically provides between 5 and 10 per cent of NEM demand. In comparison, coal generation currently provides around 60 per cent of NEM demand. Figure 3 shows price setting analysis for the NEM since January 2021 undertaken by the Australian Energy Regulator. Gas-fired generators set prices around 11 per cent of the time whereas black coal-fired plant set prices almost 50 per cent of the time.

As coal prices rose throughout 2022 and black coal-fired generators raised their offer prices, gas-fired generators maintained their offer prices above black coal, on average, including during periods when gas prices were administered in Queensland, New South Wales, and Victoria. This is because there is not enough swing gas in the east-coast gas system to significantly displace coal-fired generation. This was evidenced during the winter of 2022 when reductions in coal-fired generation led to increased gas-fired generation and a rapid increase in gas prices.

Therefore, the fundamental driver of higher electricity prices is higher coal prices, not gas prices. Capping gas prices may ease the rise in electricity prices to some degree. However, capping prices reduces incentives to supply gas and increases incentives to use gas. Therefore, gas price caps would undoubtedly significantly increase demand (especially from gas-fired power generation) and result in the rapid depletion of gas in storage. At that point, the only solution would be to ration gas to a queue of potential users, with central planners being the final arbiter on which parties would be approved to consume gas.

The international coal price is expected to remain elevated for some years. Of course, not all coal-fired power stations in Australia have coal prices linked to the international coal market. The Victorian brown-coal-fired generators and most of the black-coal-fired generators in Queensland receive coal from integrated mine-mouth operations or adjacent coal mines, at cost or on a cost-plus based formula. However, the Stanwell and Gladstone power stations have at least some coal supplies linked to international prices and the five (soon to be four with the closure of Liddell in 2023) New South Wales coal-fired power stations are increasingly being exposed to international coal prices, at least for marginal coal.

The New South Wales coal-fired power stations historically entered longer-term coal supply contracts, often on a cost-plus basis with little or no linkage to international coal prices. Often these contracts involved being a foundation customer for a new coal mine. As these long-term contracts have wound off, the New South Wales coal-fired generators have shifted emphasis to shorter-term market-priced contracts. This has been a rational response to the future uncertainty of how these stations will operate and when they might be closed, as investment in renewable energy increasingly erodes their market share. However, opening new supplies, especially in New South Wales, appears extremely unlikely, even if a power station was willing to enter a longer-term contract.

Potential solutions?

As global demand for coal continues to increase and the Australian coal supplies tighten, there are no simple solutions to lowering electricity prices. Capping gas prices will harm the gas market and rapidly lead to rationing and queueing. A better alternative is to deal with the root cause of the problem - coal prices. There are several potential solutions, but each of them has elements of ugliness from both a market and policy perspective:

1. Cap coal prices to power stations

Capping coal price to power stations would likely dissuade coal suppliers from selling them coal as selling to international buyers would be much more profitable.

2. Domestically reserve a proportion of coal for electricity generation

Domestically reserving coal, if significant enough, would force miners to supply coal to the domestic market at a much lower price than internationally. However, there would be difficulties in implementing the policy for all mines because of physical infrastructure constraints and the suitability of coal quality for burning in the power stations. These matters could be overcome by secondary trade in reservation obligations and the blending of different coals at the power stations. Enacting a domestic reservation regime would create sovereign risk issues for the New South Wales and Queensland coal mining industries. Still, these risks could be kept to a manageable level where the reservation requirements included sunset provisions. There would however be high administrative costs in managing a reservation policy in both states.

3. Provide subsidies as rebates to reduce the effective price paid for internationally linked coal

Governments (state or Commonwealth) could provide subsidies to reduce the effective price paid for coal into power stations, where prices are linked internationally. The subsidy would be based on international prices exceeding a specific value. As coal prices fall, the subsidy would fall. These subsidies could be funded from broader tax revenues or specific imposts on the coal industry (additional royalty, tax on profits, etc.). Power stations would need to demonstrate the volume of coal linked to international prices on an ongoing basis. The ratio of dollars saved in the electricity market versus the subsidy cost would be expected to be much greater than one. The complexity of implementing this approach and the fact that benefits would not be confined to one region, but would flow across the NEM, indicate that it would be better implemented nationally by the Commonwealth.

Implementing a policy of providing subsidies raises several matters:

- There is no certainty that all the benefits of the reduction in coal prices would be passed onto consumers in the form of lower electricity prices.

- There would be a requirement for a high degree of open book analysis for the entities seeking the subsidies; this implies high administrative costs in implementation.

- Raising additional taxes on the industry creates sovereign risk issues, although these risks could be kept to a manageable level where the policy and additional taxes included sunset provisions.

The above discussion indicates that there are no easy solutions to reduce electricity prices. However, any effort to lower electricity prices must focus on the root cause of the problem: increased input costs for coal fired power stations due to inflated international coal prices.

1 The Treasury (Oct 22), Budget Paper Number 1, page 57