Insights

Data and evaluation in Government services, Part III: Uplifting Data and Digital Processes

06/03/2025

This article is Part III of a four-part series on data and evaluation in government services – see Part I, Part II and Part IV for additional information on this topic.

In Part II of this series of articles we discussed the use of DDGS mapping as a starting point for understanding the impact of the Data and Digital Government Strategy (DDGS) and Implementation Plan on the operations of an Australian Government entity. Once the DDGS mapping is complete, the next step in the process is data and digital uplift.

Data and digital uplift

Following an appropriate and rigorous DDGS mapping, Australian Government entities should conduct data and digital uplift to implement each of the commitments of the Australian Government in the DDGS. Depending on the specific commitments at issue, this might require uplift of a range of data and digital processes, or supporting processes, which may include:

- uplift of data governance;

- uplift of processes for data stewardship;

- deployment of secure and scalable data architecture;

- uplift in processes for sourcing data;

- uplift of processes for reference and master data;

- uplift of processes for recording and tracking metadata;

- uplift in processes for document and content management;

- uplift in processes for sharing data;

- uplift in data integration and interoperability;

- uplift in data quality and quality assurance processes;

- uplift of privacy and ethics processes for data systems/processes;

- uplift of data security and review processes for data access;

- uplift of data modelling capabilities and business intelligence;

- merging of data capabilities with economic valuation of programs and services;

- creation/uplift of internal or public-facing data and digital platforms; and

- parallel efforts to foster the use of data and digital platforms.

Specific areas for uplift and approaches for uplift will need to be informed by the DDGS mapping that examines the application of DDGS requirements to the operations of the entity at issue. It may also be informed by broader international best practices for data and digital processes, informed by the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies1. Assessments and ratings using the OECD Digital Governance Index give information on international practice and strategic foundations across OECD countries, which can aid in identifying best practices internationally. Care is needed in this exercise owing to differences in business and regulatory environments in Australia and other countries.

Data and digital uplift should accompany evaluation processes

One of the key Initiatives in the DDGS Implementation Plan is an ongoing initiative for the Australian Centre for Evaluation (ACE) in the Treasury to embed evaluation processes into the policy development lifecycle across all government entities2. The primary aim of this Initiative is to maximise the value of data, which is one of the Missions in the DDGS. This initiative ties in with requirements under the Commonwealth Evaluation Policy3 and the ACE Evaluation Toolkit4.

ACE/Treasury have an existing high-level methodology and templates/tools for valuation, but these allow significant variation in methods and models, so the development of data-driven evaluation processes requires specialist economic expertise. For this reason, data and digital uplift for the DDGS will generally need to be augmented by parallel uplift in economic valuation and modelling.

By combining data and digital uplift with embedded processes for economic evaluation, Australian government entities may ensure that they are able to track the value of their processes and operations and report to Treasury on likely economic impacts from policy and process changes. This combination is twofold: (1) data and digital systems should be uplifted in a way that allows them to feed information into evaluation processes; and (2) economic evaluation processes may be applicable to the data and digital uplift and related policies.

Data and digital uplift should by “user-centric”

A general principle of data and digital uplift is that it should be “user-centric” (sometimes called “customer-centric”) in that uplift to systems and processes is undertaken with a view to the needs of users. This includes internal users within government entities who need to use data and digital systems for internal operations. It also includes external stakeholders and members of the general public who may access government data from available digital platforms or reports.

A basic aspect of user-centric data and digital uplift is to ensure that data is available broadly and is not siloed into systems that inhibit access and interoperability. Access to cross-functional data typically expands user possibilities both for internal and external users, allowing them to use and combine data across multiple operational areas. (This is sometimes referred to as “democratising” data access.) This is of particular importance in the context of Australian government services, since the openness of data and digital systems is the one area where Australia lags behind other OECD countries in the Digital Government Index.

Ensuring that data and digital uplift is user-centric requires an additional layer of data collection and analysis ─ namely, collection of data relating to users and their usage of systems and processes. Knowledge of users and their needs should be data-driven, so the uplift of data and digital systems will typically need to incorporate a parallel process for the collection, maintenance, analysis and actioning of data pertaining to users and their use of data and digital systems. In principle, this allows data and digital uplift to evolve in a way that is appropriate to interests, behaviours and engagement of users at all stages of the “user lifecycle”.

Data on users and their usage of data and digital systems can give important insights that aid in prioritising and driving uplift. A basic aspect of this data is that it should include both internal and external users and it should provide insight on internal data needs (for operational purposes) and external data needs. Government entities will typically have a set of statutory duties that must be actioned, requiring prioritisation of matters required for internal users to deliver core operational functions. Beyond this, there may be a broad range of internal and external users and use-purposes, which may be prioritised using information from user data. For example, user data should show the volume of usage of different systems and their importance to various internal and external processes, so that user-centric prioritisation of uplift of data and digital systems can be implemented (i.e., all other things being equal, we want to uplift systems that are used more often and are more important than systems that are used less often and are less important).

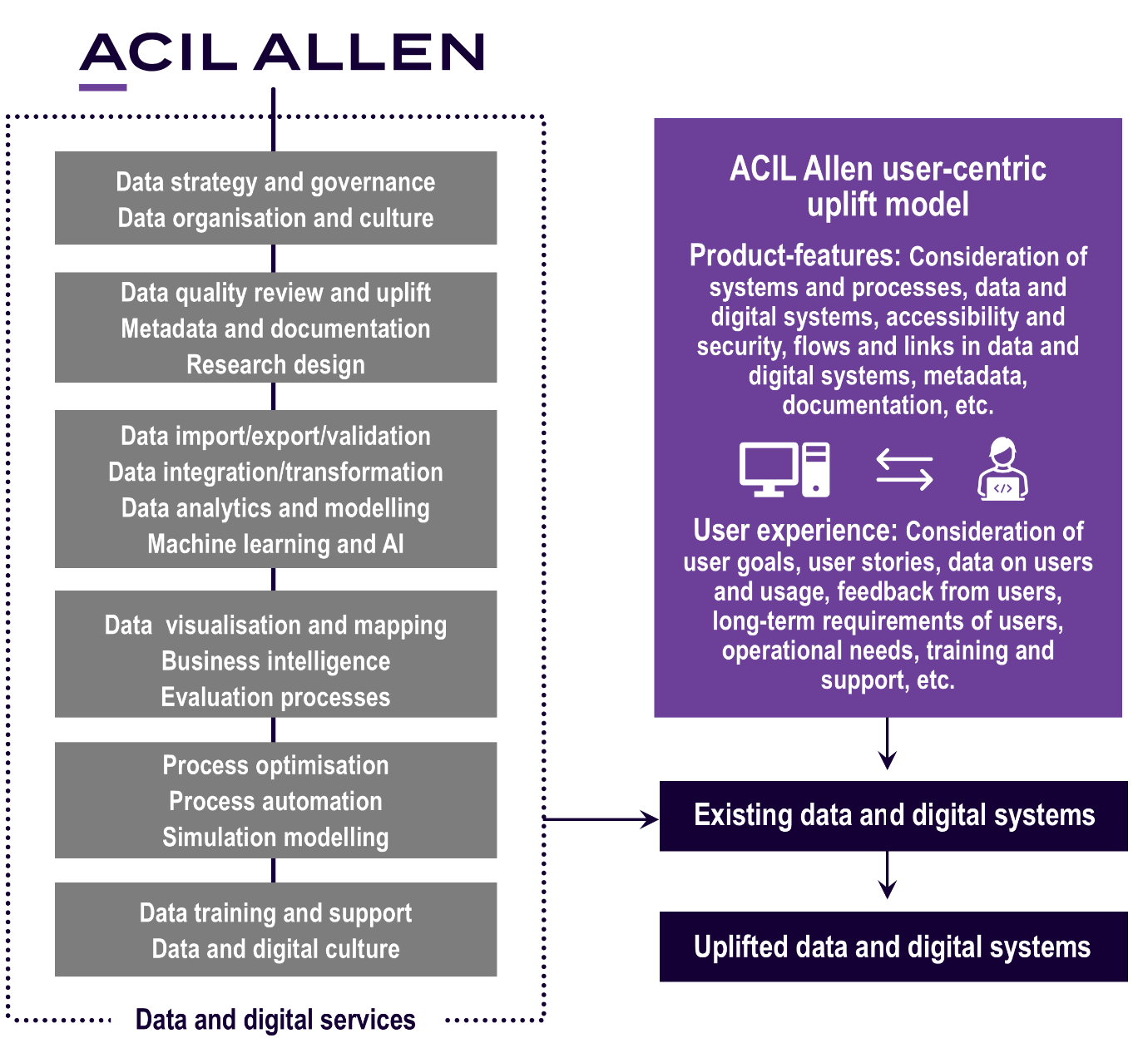

In Figure 1 below we illustrate the ACIL Allen data and digital uplift service. This service is composed of data and digital services combined with our user-centric uplift model.

Figure 1: ACIL Allen data and digital uplift service

Summary

Data and digital uplift based on an initial DDGS mapping is a key part of compliance with the missions and initiatives in the DDGS. Australian government entities must meet the vision set out in the DDGS by implementing a set of commitments and required uplift in practice by 2030. Particulars of the required data and digital uplift will depend on the operations of individual Australian government entities; this might require uplift of a range of data and digital processes and supporting processes.

Data and digital uplift should accompany evaluation processes in order to aid policy evaluation and assist governance/reporting obligations. It should also be user-centric and should include sourcing and using data on users and their usage of systems and processes. Data and digital uplift is the second step in the ACIL Allen approach to services for DDGS described in Part I of this article series. In Part IV we will examine the next step of the process.

1 Ibid, OECD (2014).

2 Ibid, DDGS Implementation plan, p. 16.

3 Commonwealth of Australia (2021) Commonwealth Evaluation Policy. Treasury Policy, 1 December 2021.

4 Commonwealth of Australia (2023) Evaluation in the Commonwealth (Evaluation Toolkit). Treasury Resource Management Guide 130. Made under the Public Governance, Performance and Accountability Act 2013 (Cth).