Insights

Data and evaluation in Government services, Part I: Implementing the Data and Digital Strategy

20/02/2025

This article is Part I of a four-part series on data and evaluation in government services – see Part II, Part III and Part IV for additional information on this topic.

Speaking to the development of statistical work in the US Government, the statistician and polymath William Edwards Deming famously quipped, “In God we trust; all others must bring data.” True to this ethos, public expectations for online services, data access, and data-driven policy evaluation are higher than ever in today’s digital age. Governments must leverage data as a strategic asset to meet these demands, providing user-friendly digital experiences and open access to data while upholding privacy and confidentiality. As organisational strategies become increasingly data dependent - with data seen as a core asset in its own right - governments must harness the value of their data as part of their strategy.1 Australia presently ranks fifth in the world based on the overall Digital Governance Index assessed by the OECD, but competition to improve data and digital services is fierce and practices are evolving rapidly.

The Challenge of Data Management in Government

Government entities hold vast repositories of data compiled from public interaction with government services. It follows naturally that government should aim for high levels of data and digital sophistication. Studies of data analytics in business and industry show that leveraging “big data” allows an organisation to understand its users, engage in process optimisation, and improve efficiency and productivity.2 Big data repositories combined with modern data processes and tools also create opportunities for strategic alignment with growing analytic capabilities.3

Unfortunately, data and digital practices within government agencies typically suffer from problems with dispersion and siloing of data, occasional duplication and inconsistency of data, lack of interoperability between data assets, and inaccessibility to outside stakeholders. Since 2014, recognition of these problems has led the OECD Council on Digital Government Strategies to direct and encourage all member countries to develop and implement digital government strategies.4

Australia's DDGS: A Vision for 2030

Consistent with the OECD resolution, the Australian Government has been developing a reform agenda for data and digital services in its agencies, with related strategy relating to data-driven evaluation. In December 2021, the Government released the Australian Data Strategy and the Digital Government Strategy, and in 2023, these strategies were amalgamated to form the present Data and Digital Government Strategy (DDGS)5, which is accompanied by an Implementation Plan that sets out implementation details for the strategy.6 The DDGS sets out a data and digital uplift strategy with a vision for uplifted services to be achieved by 2030. The vision of the DDGS is to “deliver simple, secure and connected public services, for all people and business, through world class data and digital capabilities.”7

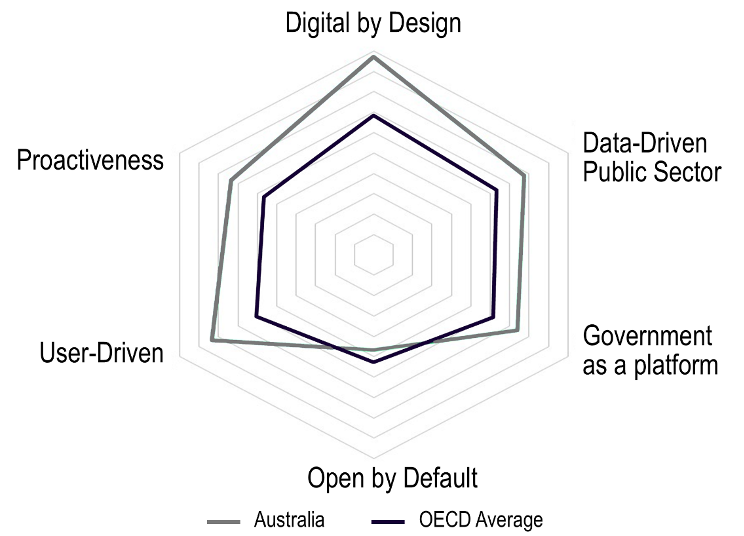

While governments often trail private industry in data practices, Australia performs well compared to other OECD countries. The OECD Digital Governance Index assesses digital governance on a six-item scale by examining whether each country has “…the necessary foundations in place to be able to leverage data and technology to deliver a whole-of-government and human-centric digital transformation of the public sector.”8 Australia ranks fifth in the world on the basis of the overall Digital Governance Index, with ratings on the six-item scale shown in Figure 1 below. At a broad level, Australia scores well on most aspects of the assessment scale, but with a lower rating for openness of data and efforts to foster the use of data to communicate and engage with users.

Figure 1: Australia and OECD ratings OECD Digital Government Index 2023 (Index scale from 0-1 going outward)

Source: OECD

The challenge for Australian Government entities

The DDGS and accompanying Implementation Plan set out five “missions” with specific initiatives planned to achieve those missions. The DDGS also includes a broad set of commitments that apply to all Australian Government entities. These entities need to be aware of the specific missions and initiatives but must also act to ensure that they meet the broader general commitments. To achieve the missions in the DDGS, the Implementation Plan sets out specific Initiatives (including programs to be implemented in various government agencies) and also sets up a governance and reporting framework involving the reporting of outcomes and metrics to the Department of Finance.

Permeating the DDGS is a strong symbiosis between embedding evaluation processes and uplifting data and digital capabilities. Good data capabilities and processes serve as a foundation to support evaluation of programs and services, and likewise, the evaluation of programs and services supports planning for data and digital uplift.

The commitments of the Australian Government in the DDGS are extensive. They apply to all government entities, from large government departments down to much smaller commonwealth entities. Whilst the commitments are extensive ─and require detailed mapping to give appropriate implementational rigour─ it is useful to mention some of the key commitments to give a flavour of the required transformation. A key commitment relates to data-driven policy and program evaluation, to wit, the Australian Government commits to “…collecting and analysing data to assess whether policies and services are achieving their intended purpose and are being implemented in the best possible way” (DDGS, p. 16). Another key commitment relates to overall maturity assessment, to wit, the Australian Government commits to “……developing tools to measure and report on the data maturity of entities and the APS as a whole” (DDGS, p. 28).

One of the biggest challenges of the DDGS is its breadth in both vision and application. It applies to all Australian Government entities, including Departments and non-corporate Commonwealth entities, as set out in the Australian Government Organisations Register (AGOR).9 Some major Departments (e.g., the Department of Finance and the Treasury) already have mature data capabilities and strong internal quantitative and data expertise, with corresponding expertise in economic evaluation. Some others have data teams who specialise in data relating to the specific operations of the Department, and digital teams who operate online and digital services, but do not have specialist economic expertise. Finally, some Departments and non-corporate entities operate at a lower level of data governance maturity and have lower levels of internal data and digital expertise to aid in implementation of these reforms. These latter entities have cause to be nervous as the deadline for implementation of the DDGS vision approaches.

What do Australian Government entities need to do?

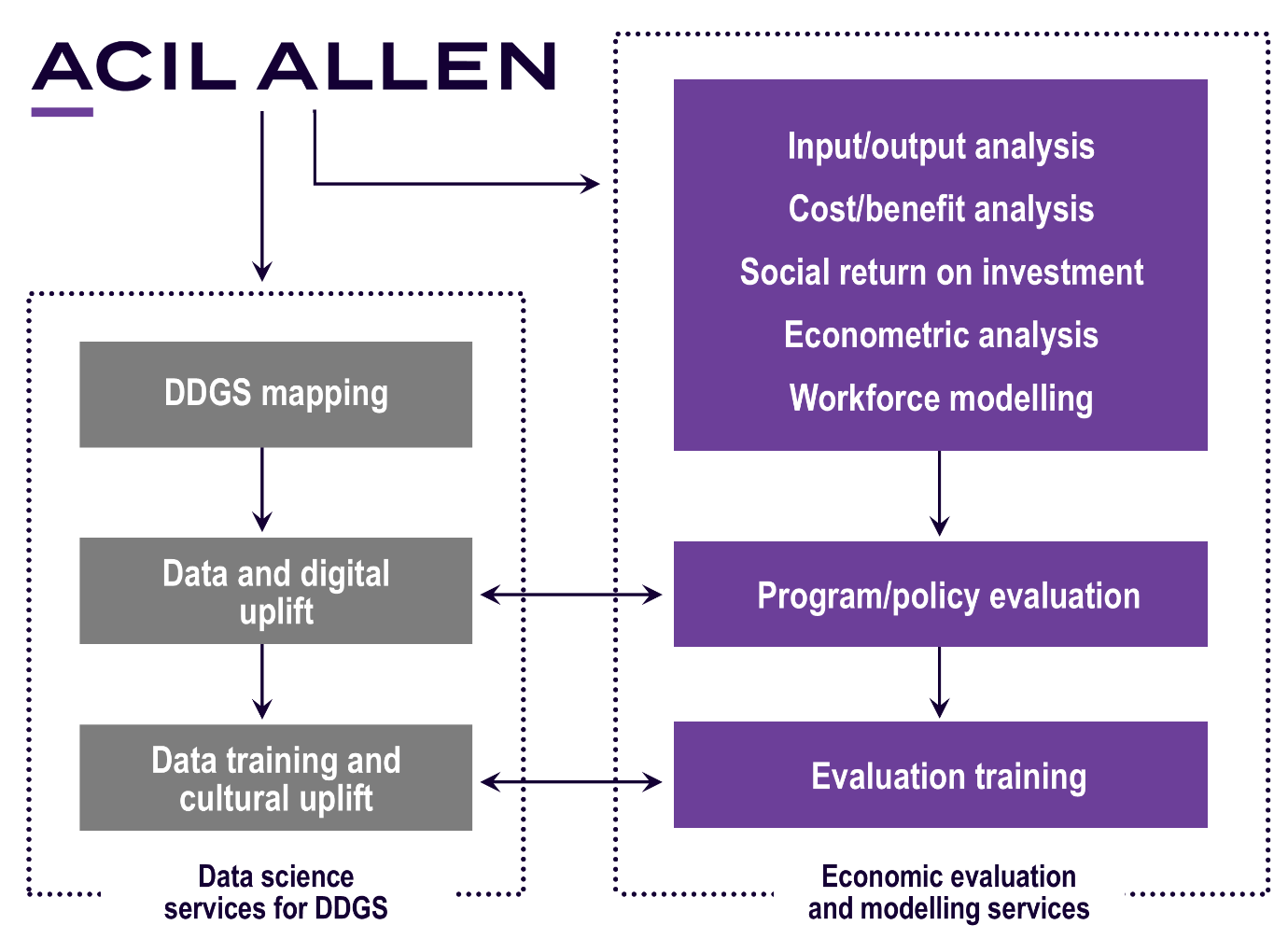

There is no time to waste, and all Australian Government entities should be taking action to implement the reform agenda in the DDGS. This requires mapping of requirements, implementation of data and digital uplift, and corresponding training and culture uplift. ACIL Allen has developed a series of services to aid Australian Government entities to implement the reforms set out in the DDGS, shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: ACIL Allen approach to services for DDGS (parallel data science services for DDGS and economic evaluation/modelling)

Source: ACIL Allen

We recommend beginning with a DDGS mapping that maps the commitments, initiatives and reporting requirements in the DDGS to the operations of the specific entity. More information about this service can be found in Part II of this series of articles.

After DDGS mapping, we recommend engaging in data and digital uplift to implement each of the commitments of the Australian Government in the DDGS. Depending on the specific commitments at issue, this might require uplift of data governance, deployment of secure and scalable data architecture, uplift of privacy and ethics processes for data systems/processes, uplift in processes for sourcing and sharing data, uplift and merging of data capabilities with economic valuation of programs and services, creation/uplift of data and digital platforms, and uplift of public-facing data and digital facilities and parallel efforts to foster the use of data. More information about this service can be found in Part III of this series of articles.

Irrespective of the particulars of the data and digital uplift, it is necessary to ensure that staff skills and work practices maintain pace with uplifted service needs. To ensure this, we recommend engaging in training and culture uplift to update and improve data and digital training for staff, and put practices in place to develop and maintain an innovative and data-savvy culture. More information about this service can be found in Part IV of this series of articles.

Because of the link between data and digital uplift in DDGS, and key implementation requirements relating to program evaluation and reporting, our approach uses both data science services for DDGS and economic evaluation/modelling services. Data and digital uplift is informed by program/policy evaluation requirements and processes. Evaluation is ─in turn─ informed by a suite of economic and econometric methods implemented to satisfy the requirements of the Commonwealth Evaluation Policy.

Implementation requires data and economic expertise

The DDGS involves the close relationship between data and digital uplift and evaluation processes. Embedding data-driven evaluation processes is a core part of the strategy and it appears in several key commitments of the Australian Government. Because of the symbiosis between data and evaluation elements, implementation of the DDGS should be undertaken with the aid of strong expertise in data science and economic evaluation.

Implementation of DDGS mapping, data and digital uplift, and training and culture uplift, all require consideration of the surrounding context of data and digital services in modern governments. This requires consideration of the vision and missions of the DDGS but also broader international best practices for data and digital uplift. Instruments like the OECD Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies form a part of broader international practice in data and digital government strategy.10 Likewise, assessments and ratings using the OECD Digital Governance Index give information on international practice and strategic foundations across OECD countries. Comparative analysis with other OECD countries can inform best practice and aid in uplift.

Although government is not in the same competitive position as private business, and is subject to additional obligations and constraints, additional insight on data strategy and efficiency may still be gleaned from the examination of literature on data strategy in business.11 In particular, uplift of data strategy can be informed by literature looking at the conditions for when data creates efficiency and productivity gains and a resulting competitive advantage.12 Assistance to government entities may also be informed by broader experience helping businesses and industry to implement data processes and data uplift in a practical and evidence-based way. This requires both data and economic expertise and experience.

1 Lee, Y., Madnick, S., Wang, R., Wang, F. and Zhang, H. (2014), A cubic framework for the chief data officer: succeeding in a world of big data. MIS Quarterly Executive 13(1), pp. 1-13.

2 See e.g., Wamba, S.F., Gunasekaran, A., Akter, S., Ren, S.J., Dubey, R. and Childe, S.J. (2017) Big data analytics and firm performance: effects of dynamic capabilities. Journal of Business Research 70, pp. 356-365; Müller, O., Fay, M. and Von Brocke, J. (2018) The effect of big data and analytics on firm performance: an econometric analysis considering industry characteristics. Journal of Management Information Systems 35(2), pp. 488-509.

3 See e.g., Constantiou, I.D. and Kallinikos, J. (2015) New games, new rules: big data and the changing context of strategy. Journal of Information Technology 30(1), pp. 44-57; Akter, S., Wamba, S.F., Gunasekaran, A., Dubey, R. and Childe, S.J. (2016) How to improve firm performance using big data analytics capability and business strategy alignment? International Journal of Production Economics182, pp. 113-131; Côrte-Real, N., Ruivo, P., Oliveira, T. and Popovic, A. (2019) Unlocking the drivers of big data analytics value in firms. Journal of Business Research 97, pp. 160-173.

4 OECD (2014) Recommendation of the Council on Digital Government Strategies. OECD/LEGAL/0406 (adopted on 15 July 2014 ─ in force).

5 Australian Government (2023) Data and Digital Government Strategy.

6 Australian Government (2023) Data and Digital Government Strategy – Implementation Plan.

7 Australian Government (2023) Data and Digital Government Strategy, p. 5.

8 OECD (2023) OECD Digital Government Index. OECD Public Governance Policy Papers, p. 8.

9 Department of Finance (2024) Australian Government Organisations Register – Dashboard. Quarterly Report, 31 December 2024.

10 Ibid, OECD (2014).

11 See e.g., Fleckenstein, M. and Fellows, L. (2018) Modern Data Strategy. Springer, pp. 35-54.

12 See e.g., Hagiu, A. and Wright, J. (2020) When data creates competitive advantage, and when it doesn’t. Harvard Business Review(Jan-Feb 2020); de Medeiros, M.M., Maçada, A.C.G. and da Silva Freitas Junior, J.C. (2020) The effect of data strategy on competitive advantage. The Bottom Line 33(2), pp. 201-216.