Insights

Prosperity, productivity and good policies

08/09/2025

Australia's path to sustained prosperity

There has been much talk about the need for policies to raise Australia’s productivity growth, particularly in the wake of the Economic Reform Roundtable. Our deep interest in these productivity debates is in raising and maintaining Australian prosperity – lifting the average living standards and wellbeing of Australians.

The need to secure our living standards is pressing. They are at risk from Australia’s declining productivity growth rate and the highly volatile and uncertain international economy.

Prosperity depends on productivity. Productivity grows the economy. Higher living standards rest on higher productivity. History tells us that to make major reforms, we need:

- public policies that lift productivity and provide clear net benefits

- legitimacy in the electorate – broad support for these policies

- adjustment assistance for those workers and businesses that bear the costs

- commitment to implement, sustain and evolve them over time.

In this insight piece we canvass three questions:

- What has driven Australia’s prosperity?

- How does productivity growth lift prosperity?

- What policies lift productivity growth?

What has driven Australia’s prosperity?

Our prosperity didn't happen by accident. Professor Ian McLean's1 research suggests that Australia's economic success rested on three enduring pillars that remain relevant today:

- Our natural resource abundance (both renewable and non-renewable) which has consistently provided export advantages, from the 1850s gold rush to the recent mining boom.

- Our institutional adaptability. Australia has demonstrated an exceptional capacity to innovate our institutions and adapt to changing circumstances.

- Our policy responsiveness. Time and again, our ability to devise and implement growth-enhancing policies in response to major economic shocks has set us apart from less successful resource-rich nations.

These strengths enabled us to navigate an extraordinary series of economic disruptions over the past 50 years, including:

- stagflation in the 1970’s and early 1980’s

- the stock market crash of 1987

- the Asian economic crash of 1997

- the large increase in Australia’s terms of trade from China’s demand for iron ore, coal and other commodities from the early 2000’s which substantially lifted real incomes

- the Global Financial Crisis of 2007

- disruption from the COVID-19 pandemic in international and domestic and social economic from 2000

- very recent shocks to the international trading system from international conflicts and the imposition of tariffs by the United States.

Historically, our institutions and system have enabled us to respond flexibly and effectively to such shocks. We have a history of devising and implementing necessary economic policies that have raised economic growth. The profound policy shifts of the 1980s shows this adaptability. When Australia floated the exchange rate, slashed tariffs, and launched comprehensive microeconomic reforms, these decisions weren't just technical adjustments, they were changes that reshaped our economy and prepared us well for the Asian economic crash of the late 1990’s when the floating exchange rate cushioned Australia’s economy.

Threatening the foundations: Australia’s productivity decline

Our policy responses over the past 50 years made a large contribution to maintaining Australia as a high-income, resource-based economy among the world’s advanced economies. However, the very prosperity that defines modern Australia is threatened by a serious underlying problem. Our productivity growth rate – the engine of rising living standards – has been steadily declining.

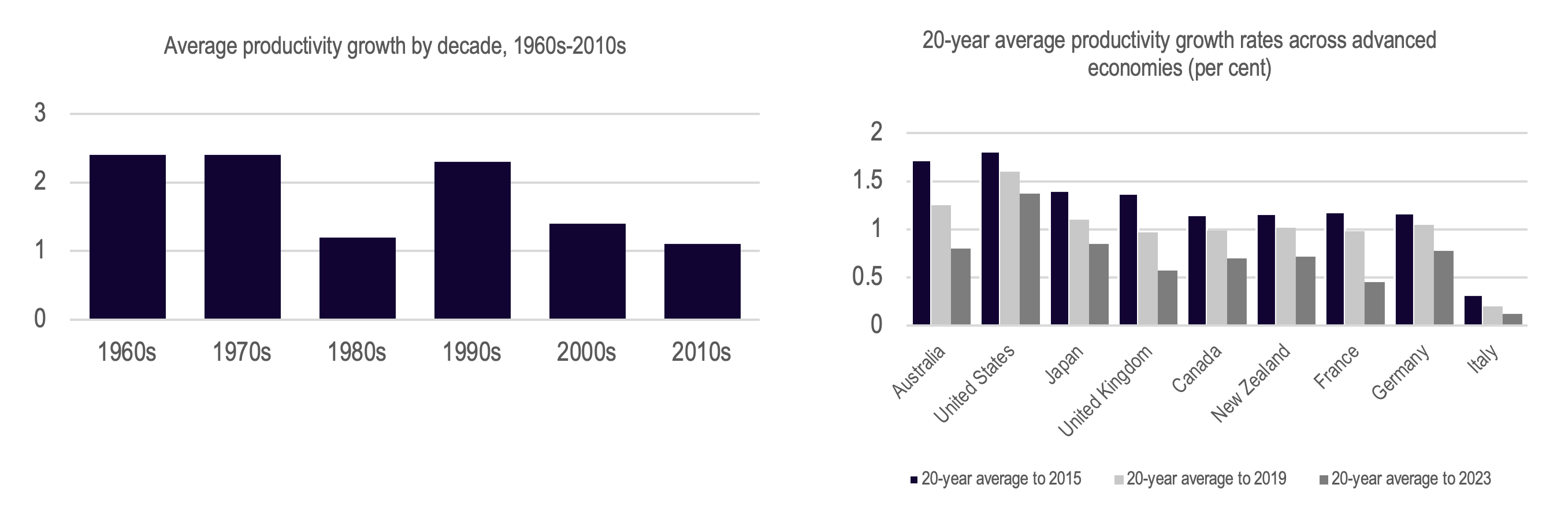

According to Treasury analysis prepared for the Economic Reform Roundtable (see Figure 1), there are some concerning trends:

- Australia's labour productivity peaked in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1990s

- the 2010s marked our lowest average productivity growth in decades

- while we still outperform many advanced economies (Australia’s level of average labour productivity growth has been higher than most), our rate of decline in productivity growth has been steeper than most.

Productivity directly determines our prosperity. When productivity growth slows, so does our capacity to maintain and improve living standards without simply working longer hours or consuming more resources.

Figure 1

Source: Australian Government Economic Reform Roundtable 2025, Productivity.

How does productivity growth lift prosperity?

The relationship between productivity and prosperity is simple: prosperity increases when economic growth outpaces population growth. Economic growth comes from two sources:

- Adding more inputs (more workers, more capital, more resources) increases the size of the economy in proportion to the size of the inputs.

- Productivity growth, which is our ability to get more output from the same inputs.

The first approach has natural limits. The second – productivity growth – is where the magic happens. It's about working smarter using better technology and creating additional value in the economy, not just harder.

Labour productivity (output per hour worked) rises through better education and skills development (which lifts the quality of labour input and increases the scope and flexibility of workers’ jobs), and capital investment per worker. Multifactor productivity captures our ability to generate more output from all our inputs combined (including labour, capital and natural inputs), through adopting new technology, research and development, invention and innovation, among other sources. Growing multifactor productivity is at the core of growing the economy.

The Commonwealth Treasury’s analysis of Australia’s labour productivity shows that, since 1900, roughly half of Australia's labour productivity gains have come from increasing capital per worker. The rest came from investment in higher skills and education and crucial multifactor productivity improvements following the microeconomic reforms of the 1990s.

Our natural endowments add complexity to this story. Over the last 200 years exports (whether gold in the 1850s, wool during the Korean War, or iron ore in the 2000s) delivered prosperity gains equivalent to major technological breakthroughs. However, commodity booms are usually short and temporary, and export prices are volatile. The economic institutions and policies that help us adapt to external shocks have been Australia's real competitive advantage over the past two centuries.

Today, the international trading system that underpinned our recent prosperity faces unprecedented disruption. From trade wars to supply chain fragmentation, the external environment that supported our growth model in the past is under stress.

What policies lift productivity growth?

While the economic case for productivity reform is well-established, the policy challenge lies in identifying which specific reforms will deliver measurable results and developing effective implementation strategies that ensure sustainable outcomes.

Two pathways to productivity growth

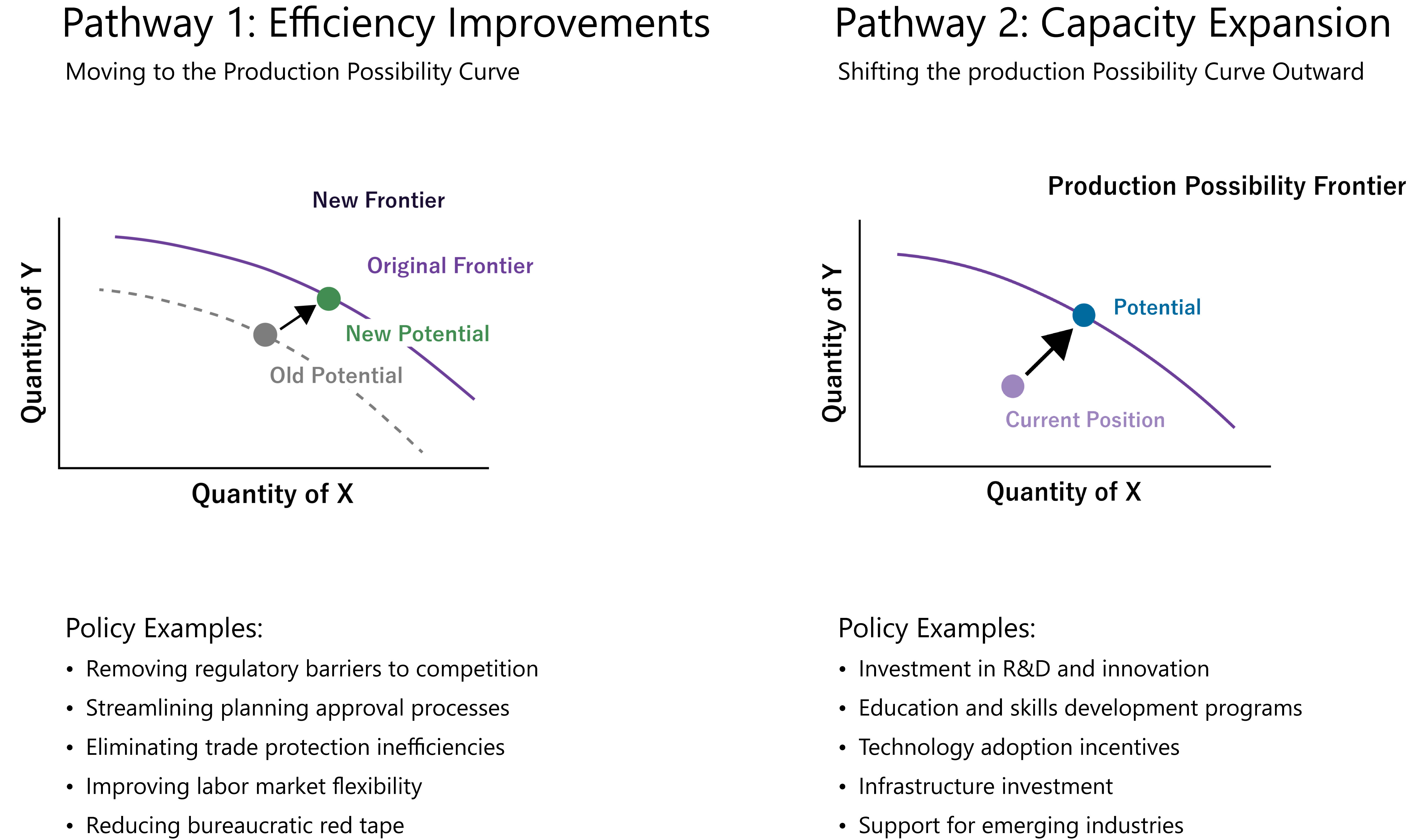

There are many ways to assemble a pro-productivity agenda. At a high level, policies that support productivity growth generally fall into two categories (see Figure 2):

- Policies that move the economy closer to its potential output. These focus on removing barriers that stop us from making the most of our existing resources, reducing waste and inefficiency in how labour, capital, and natural resources are allocated. A central strategy is to ease or eliminate obstacles that prevent inputs from flowing to their most productive uses. Competitive markets and price signals are usually the most effective mechanisms for this, and most reform policies target these barriers.

- Policies that expand the economy’s potential output. These aim to lift the economy's fundamental capacity to generate valuable outputs, typically through fostering technological progress, encouraging innovation, and building capabilities.

Both matter, but they require different approaches and deliver results over different timeframes.

Figure 2

Source: ACIL Allen.

The levers and tools available to the government that move the economy closer to its potential output are extensive and include the following.

- Removing barriers to efficient resource allocation by strengthening competition and markets – in the 1990s, Commonwealth and state governments (backed by financial incentives) undertook significant reforms of public enterprises and competition policy. While progress was uneven, the reforms delivered real benefits. Further opportunities remain, particularly in reforming national energy markets.

- Lifting the productivity of inputs, especially labour, through capability building – this includes sustained investment by both businesses and government in education, skills, and workforce development to raise labour productivity and secure better-paid jobs. Historical examples, such as Victoria’s investment in public education and Mechanics Institutes after the Gold Rush, show how capability-building can support long-term prosperity. Labour market reforms that enhance flexibility can also lift productivity by reducing the natural rate of unemployment.

- Ensuring the tax system is efficient and minimises distortions – major tax reform opportunities exist across all levels of government. These include shifting reliance from personal income taxes to less distortionary taxes, modernising taxes for a service-oriented economy, and addressing the under-taxation of multinational businesses, especially large technology firms. Reliance on stamp duties by most states and territories, for example, raises mobility costs in the labour market. However, history shows that tax reform is politically difficult, as illustrated by the long road to introducing the Goods and Services Tax.

- Making regulation and regulatory systems more efficient, streamlined, and fit for purpose – while regulation is essential to protect public interests and reduce harms, regulatory frameworks often evolve incrementally and become outdated, inefficient, or slow. Obsolete or poorly designed regulations can stifle innovation and delay the adoption of new technologies. Ongoing reform is needed to resolve competing interests more effectively and accelerate decision-making, both within and across jurisdictions. Planning and building approvals stand out as high-priority areas for reform to boost housing supply. The Productivity Commission has suggested that artificial intelligence could help simplify and speed up these processes. Similar opportunities exist for resource project approvals, ensuring our natural endowments continue contributing to prosperity.

- Strengthening government investment processes – major public investments should be underpinned by robust business cases to ensure they deliver productivity gains.

- Boosting the efficiency of cities – Australia’s largest cities, which generate the bulk of GDP, must operate efficiently to support growth. Infrastructure investment (in transport, energy, water, and related services) is critical, especially in light of the high levels of immigration Australia has experienced in recent years.

Policies that increase the ongoing rate of productivity growth and grow our economy's potential include the following:

- ongoing investment in education and training

- support for research, development, and innovation, particularly strengthening links between business and our research institutions

- policy coordination, alignment and collaboration within and between governments, industries and sectors.

The challenge with these policies is complexity. Unlike removing regulatory barriers (where benefits often flow quickly) education, training, innovation and coordination investments deliver returns over longer timeframes and with less certainty.

Doing reform successfully

Major reforms in these areas are inherently difficult. The levers of productivity reform are sticky, and care will need to be taken regarding the speed and scale that changes are chosen and implemented. Choosing the right starting point can create momentum for broader change — as seen after the floating of the exchange rate, which arguably paved the way for tariff reductions and wider microeconomic reforms.

Making and sustaining major reforms to boost productivity also depends on their legitimacy in the eyes of the electorate. Too often, productivity-enhancing policies have been derailed by partisan conflict or the loud opposition of groups whose interests are threatened. Building a mandate and broad public support is therefore essential (and the first challenge). Focusing on widely recognised priorities and problems helps establish the compelling case for reform. Today, the housing shortfall amid rapid population growth is one such priority; tax reform and energy are two others.

The next challenge is persuading the electorate (and, where necessary, other levels of government) of the value and necessity of robust, credible reform policies that deliver clear net benefits. Listening to those most affected by proposed changes is crucial, especially when reforms require collaboration between two or more levels of government and real costs are borne by some workers and sectors.

Finally, supporting workers who bear the costs of adjustment is both fair and politically necessary. Using part of the general gains from reform to ease transition costs helps secure broader acceptance, and it is important that it is done well. For example, the tariff reforms of the 1980s included adjustment assistance and reskilling for displaced workers, while the introduction of the GST in the 1990s provided compensation for key groups most affected.

Present opportunities and the pathway forward

In the aftermath of the recent Economic Reform Roundtable, the Treasurer identified several immediate opportunities:

- introducing road user charges for electric vehicles to contribute to road upkeep

- abolishing nuisance tariffs

- reducing complexity in the National Construction Code

- accelerating new environmental approvals legislation to speed up project approvals

- facilitating modular construction methods to increase the pace of homebuilding

- harmonising licensing standards across states and territories

- developing an artificial intelligence plan for the Australian government.

Each of these measures fits within the broad category of productivity-enhancing policies. None on its own is likely to deliver a transformative impact, but all are worthwhile. Together, they illustrate the point that major reforms are relatively rare, while ongoing smaller, targeted reforms can make important, meaningful contributions.

The Treasurer also foreshadowed consultations on broader tax reform, with objectives to make the tax system fairer for workers and younger Australians, more attractive for business investment, and simpler and more sustainable. If advanced, this could represent a major reform.

Looking ahead, the Productivity Commission will report in December on its inquiry into Boosting Australia’s Productivity. The inquiry addresses five key areas:

- Creating a more dynamic and resilient economy

- Building a skilled and adaptable workforce

- Harnessing data and digital technologies

- Delivering quality care more efficiently

- Investing in cheaper, cleaner energy and the net zero transition

Some of the Commission’s draft recommendations have already been reflected in the Economic Reform Roundtable discussions. Its final report will provide another opportunity to shape the next phase of Australia’s economic reform agenda.

Finally, it will be important to think both holistically and individually about the opportunities and challenges facing governments as they seek to increase productivity growth through reform. The matrix below provides some illustration of how the policy levers we have identified in this article relate (at least conceptually) to industry and sectors that will deliver productivity growth and ultimately future prosperity. The matrix shows the immense reform task facing governments and industries alike.

| Productivity Gains |  Low Impact/limited direct productivity effects Low Impact/limited direct productivity effects  Medium Impact/moderate Medium Impact/moderate  High impact/major productivity gains High impact/major productivity gains | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sector/Policy Lever | Competition & markets | Regulatory reform | Tax efficiency | Skills, education & labour market flexibility | Infrastructure investment | R&D, science & innovation support | Trade & investment |

| Construction & housing | – Enable modular construction competition | – Reform stamp duties | – Address skills shortage | – Transport links to new developments | – Use AI to simplify and expedite planning approval processes | ||

| Energy | – Complete NEM reform | – Streamline renewable energy approvals | – Carbon pricing mechanisms – Renewable energy incentives | – Clean energy transition skills | – Storage systems | – Clean energy R&D | – Pursue free trade agreements with Europe, the UK, and Asia |

| Utilities (inc. waste) | – Water pricing reform | – Waste levy optimisation | – New certifications and training programs | – Infrastructure investments for circular economy (recycling facilities, waste processing facilities) | – Development of sustainable alternatives (e.g. for plastic packing and other products) | ||

| Transport & logistics | – Freight, port competition | – Autonomous vehicle regulation – Drone delivery approvals | – EV road user charges | – Electric vehicle technicians | – Road, rail, port capacity | – Autonomous vehicles | |

| Financial services | – Payment system competition | – Data security and privacy-aware compliance | – Superannuation tax reform | – AI in finance | |||

| Healthcare | – Health services competition | – Ensuring quality and safety in service delivery | - Health insurance tax | – Harmonised workforce training & credentialization – International worker recognition – Telehealth workforce | – Digital health systems – Aged care facilities | – Medical research AI diagnostics | – Health technology exports – Pursue free trade agreements with Europe, the UK and Asia |

| Education & Training | – VET and higher education competition | – Micro-credentials regulation | – Employer training incentives –Student load optimisation | – Digital skills integration – Rapid reskilling programs – Micro-credentialing | – Campus and facilities upgrades | – Digital, immersive & AI-powered training tools and techniques | |

| Social services | – Disability services competition in thin markets | – Aged care standards reform – Disability service regulation –Childcare regulation | – Aged care financing | – Social care workforce training – Mental health skills | – Aged care facilities – Disability accessible infrastructure – Community service centres | – Assistive technology | |

| Manufacturing (inc. advanced manufacturing) | – Product standards harmonisation | – R&D tax incentives – Manufacturing investment allowances | – Advanced manufacturing skills – Automation training | – Testing facilities and pilot plants | – Robotics/automation technology – Advanced manufacturing R&D | – Pursue free trade agreements with Europe, the UK and Asia | |

| Mining & resources | – Environmental approval streamlining | – Ports and transport networks | – Mining automation | – Pursue free trade agreements with Europe, the UK and Asia | |||

| Agriculture | – Drought, flood and other subsidies to producers | – Effective biosecurity arrangements | – Tax incentives for primary producers | – Sustainable farming practices – Agriculture technology skills – Agricultural visa systems | – Inland rail and intermodal freight hubs | –Agtech innovation | – Agricultural export agreements with Europe, the UK and Asia |

| Digital Technology | – Platform regulation – Data portability | – Privacy regulation – AI governance | – Tax and investment incentives for commercialisation | – AI and data science education – Skilled visas and migration programs | – Data centres & innovation hubs | – AI research – Quantum computing – Digital innovation hubs | – Export grants and incentives |

1 Ian W. McLean (2013), Why Australia prospered – the shifting sources of economic growth, Princeton, Princeton University Press

2 For this article innovation is defined as something that is new or improved to create significantly added value either directly for the enterprise or indirectly for its customers (Carnegie and Butlin (1993) Managing the Innovating Enterprise – Australian companies competing with the world’s best, Business Council of Australia Melbourne).

3 See M.W. Butlin and C.J. Findlay, Dilemmas in Regulation, Australian Economic Review forthcoming.