Insights

Australia’s food security

23/08/2022

Australia is consistently rated as one of the most food secure nations in the world1 . Diversified production, mature supply and delivery chains, and reasonable access operating in a stable society, provide cornerstones for domestic food security and a vibrant export industry.

The two sides of food security: availability and accessibility

Australia reliably produces and distributes enough safe food to feed 70 million people2 made up of a variety of food types. The 10 percent of food we import is driven by consumer preference rather than necessity3.

But producing ‘enough’ is not enough. Recently there have been shortages in foods we take for granted as always being there. Well-known shocks such as fires, floods, and drought in Australia, the significant global supply chain disruptions created by COVID-19, and the war in Ukraine, along with trading partner disputes have all impacted our food security.

Today our biosecurity system is working hard to prevent the potentially devasting impact of varroa mite (bees), and diseases such as foot and mouth (livestock), and LSD - Lumpy Skin Disease (cattle and water buffalo). East coast floods devastated seasonal leafy greens and disrupted transport logistics this winter. While supply chains are still recovering from COVID-19, shortages in labour4 and other key inputs such as AdBlue5 (an additive required for diesel engines) and even sea container shortages continue to impact them6.

While supply chains will eventually adjust, and the foods will become available again, it may not necessarily be at the same shelf price7. For example, floods reduce production and make it harder to get food to market, which has seen supply chains increase inventory in response. Storing more food in warehouses, retail stores, and homes allows everyone to ride out shortages, but this is not an option for perishable fresh produce such as vegetables, which is why lettuces became so expensive.

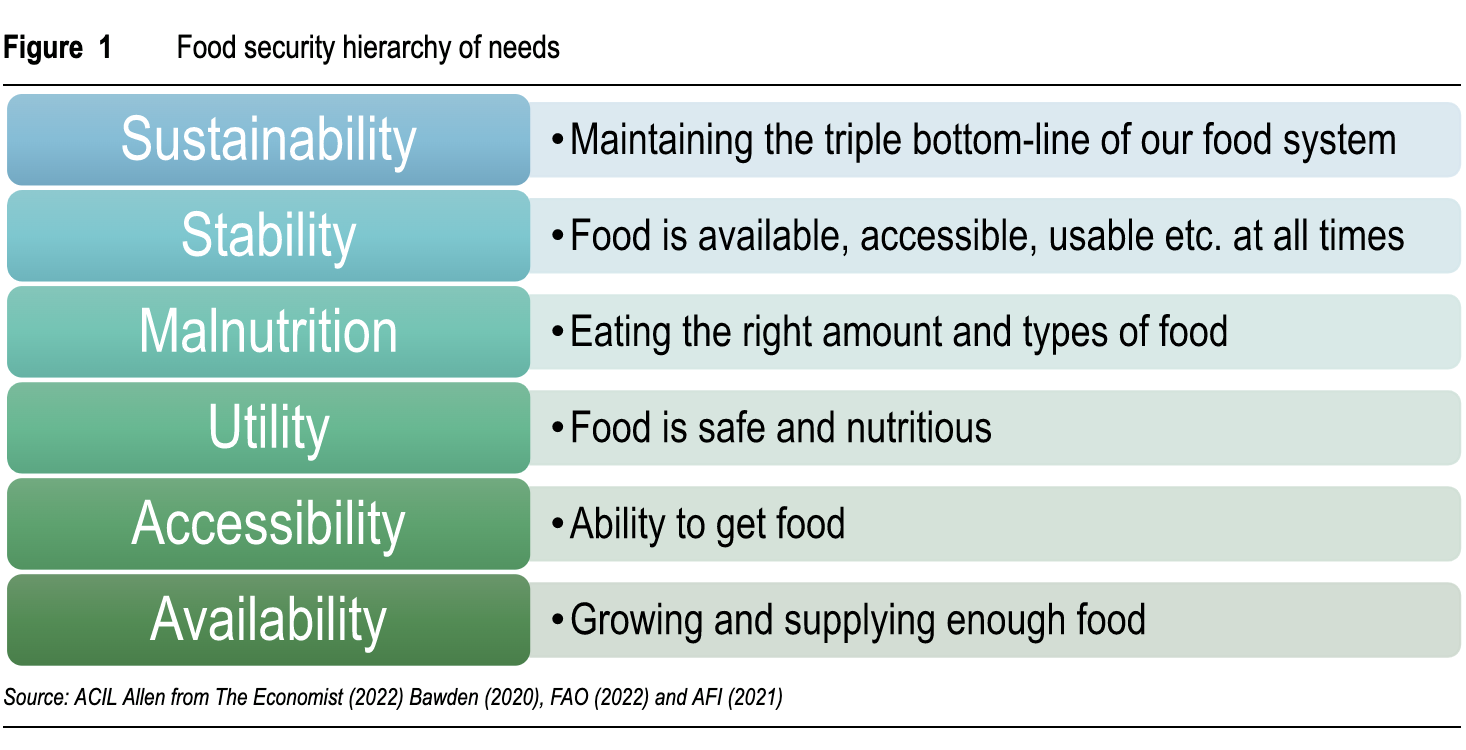

The flipside of food security is food insecurity which is about access, diet, and stability8. Local availability, pricing, mobility, transport limitations, and the ability to store/prepare food at home all impact the amount of food many Australians can access, as well as the nutritional qualities of the foods they do access9. In parts of Australia, 20 percent or more of the population experience food insecurity, including for Indigenous and unemployed people, single-parent and rental households, low-income earners, and young people10. Others who are susceptible include the frail, those lacking transport, people abusing substances, and some Culturally and Linguistically Diverse groups (including refugees).

Many Australians experienced short periods of increased food insecurity through the COVID-19 pandemic due to reduced availability and ability to access secure food supplies. Similarly, communities experienced short periods of food insecurity following floods and other environmental shocks.

Australia is a modern developed nation with significant capabilities that is working to improve our food system. The recent supply shocks and insecurity around availability highlight that there is room for further improvement.

Minimising waste

Producing more from less is one - if not the - core foundation of Australia’s success in food production. Productivity gains underpin the sustainable competitiveness of food industries, businesses, and their exports. However, there is still some 7.3 million tonnes of food worth $20 billion which is wasted every year across the food system11. Nearly half is wasted because food can’t be sold by growers or retailers because supply exceeds demand at times, or food does not meet market standards for sale even though it is safe to eat. Most of the remaining is wasted in processing or due to households disposing their surplus food and leftovers.

Much of the technology and practice needed to improve security of food supply is currently available. More is coming through endeavours in Australia and overseas. Goals such as no net biodiversity loss, carbon neutrality, circular economies, doubling value (adding) and halving waste provide powerful aspirational targets. All are important, all have potential, all compete for our support/attention, all have trade-offs, but can we do all at once? If we can’t, which one (or more) can we do and when?

Resilience to shocks

Resilience to future shocks has become a catalyst for improving food security. The cumulative impact of repeated shocks challenges us to ask whether business as usual will suffice? The agricultural sector is still recovering from the COVID-19 disruption (especially the supply of labour and access to key inputs like fertilisers and fuel). Other shocks are expected to return in greater frequency and intensity in the future (e.g., extreme weather events, biosecurity breaches, and geopolitical events impacting key inputs).

The broader question of whether Australia has sufficient resilience is being asked widely and not just in relation to food. As the NSW Flood Inquiry noted: individuals, households, businesses, communities, services, and governments all need to improve preparedness rather than relying on (assisted) recovery alone12. The need for action at these levels is also applicable in relation to food security.

The practical lens to improving resilience for businesses involved in food production, distribution and retail is focusing on continuity of food supply. A secure food system relies on businesses that can supply during adverse events and despite shocks. The opportunities extend beyond an individual business to the way value chains, government and businesses organise themselves. Increasing resilience will likely include increasing inventories and increasing diversity of warehousing. This will result in a permanent increase in supply chain costs but will reduce the more extreme costs associated with disruptions to supply.

Lifting nutrition nationally

Improving nutrition requires a sustained and multi-faceted approach. Individuals and populations face different food hierarchy challenges and have different preferences. Care must be taken to ensure policies and programs take into account individual preferences and are not unnecessarily coercive. Addressing an individual or households contributors of food insecurity does not address the challenge alone. Food insecurity often coincides with economic, health and housing insecurity, and other hardship. Public policy and community level solutions can assist in addressing food insecurity for all Australians13.

The array of food (safety) standards, dietary guidelines, welfare initiatives, and education programs we have developed as a nation are distributed broadly across our Federation. Not for profits, government ministries, policies, and departments all contribute and some - like food safety - are non-negotiable essentials, yet Australia lacks a national nutrition plan. Other comparable nations have effectively used national nutrition plans14 as the focus to reduce food insecurity and been able to achieve efficiencies from coordinated efforts in service provision and mitigating the impact of COVID-1915.

Integrating ESG and GM

Environmental and Social Governance has strengthened markedly in recent years beyond meeting selected preferences and brand differentiation. ESG is becoming a capital and market access requirement for the production, trade, and export of food16 17. This all comes at a time when rising population and greater consumption by many is increasing demand for food and land, and the water available for food production continues to decline18 19.

New technologies are required to overcome increasing environmental constraints on food production (e.g., the changing climate, unreliable water supply, and increasing pest/disease prevalence and resistance). Genetic modification plays a role in accelerating foods which can grow despite these conditions. It also plays a role in ESG by allowing us to produce safer food with fewer resources and in a way that reduces or minimises environmental harm. If markets and society accept and allow ESG and GM to come together, the potential benefits are enormous.

A way forward

Australia’s food system is a national asset requiring ‘constant gardening’ to reduce imperfections and vulnerabilities. Recent shocks highlight the societal impact and economic cost that insecure food supply and availability has on Australia. That is borne from the paddock-to-plate system as well as government and the finance (insurance) sector that underwrites it.

Improving performance and resilience across the food system has potentially enormous benefits but requires a coordinated effort across the supply chain and government policy setting. Questions that Australia needs to address include:

- How much effort should we put into increasing our national self-reliance for all parts of the food production chain?

- Are we prepared to shorten the supply chains to market and face the costs of doing so (more inventory, more diversified warehousing closer to consumers and creating opportunities for growing more food hyper-locally)?

- Should we strategically intervene (governments) to move some high-value food production systems to safer/different locations (which will have both financial and social costs)?

- Should we develop a national nutrition plan to complement our aspirations for a $100 billion agriculture20 and $200 billion food and agribusiness21 sector by 2030?

References

[1]The Economist (2022) The Global Food Index https://impact.economist.com/sustainability/project/food-security-index/

[2]ABARES 2020, Australian food security and the Covid-19 pandemic, Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics and Sciences, Canberra. CC BY 4.0. https://doi.org/10.25814/5e953830cb003.

[3] ibid

[4] ABS (2021) Job Vacancies, May 2022. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/labour/jobs/job-vacancies-australia/may-2022

[5] ABC (2022) Adblue production increases after shortage. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-01-24/australian-adblue-produduction-increases-after-shortage/100778316

[6]ACCC (2022) Global container trade disruptions leave Australian businesses vulnerable. https://www.accc.gov.au/media-release/global-container-trade-disruptions-leave-australian-businesses-vulnerable

[7]Trading Economics (2022) Australian Food Inflation Index. https://tradingeconomics.com/australia/food-inflation

[8]FAO (2022) Hunger and https://www.fao.org/hunger/en/

[9]Foodbank (2021) The Hunger Report https://www.foodbank.org.au/hunger-in-australia/the-facts/?state=nsw-act

[10]Mitchell Bowden (2020) Understanding food insecurity in Australia CFCA PAPER NO. 55 https://aifs.gov.au/resources/policy-and-practice-papers/understanding-food-insecurity-australia

[11]FIAL (2021) Reducing Australia’s Food Waste by half by 2030. https://www.fial.com.au/sharing-knowledge/food-waste

[12]NSW Government (2022) Full Report of the NSW Floods Inquiry https://www.nsw.gov.au/nsw-government/projects-and-initiatives/floodinquiry

[13]Bawden op. cit.

[14]WHO (2015) European Food and Nutrition Action Plan 2015–2020. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/329405

[15]European Commission (2021) Action plan on nutrition: Sixth progress report April 2020 – March 2021. https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/publication/action-plan-nutrition-sixth-progress-report-april-2020-%E2%80%93-march-2021_en

[16]AFI (2021) Australian Agricultural Sustainability Framework. https://www.farminstitute.org.au/product/aasf-australian-agricultural-sustainability-framework/

[17]NFF (2021) Australian Agricultural Sustainability Framework https://nff.org.au/programs/australian-agricultural-sustainability-framework/

[18]FAO (2022) Food Outlook – Biannual Report on Global Food Markets. https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cb9427en/#:~:text=In%20view%20of%20the%20soaring,of%20food%20markets%20in%202022.

[19]FAO (2022) The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World. [1] https://www.fao.org/3/cc0639en/online/cc0639en.html

[20]NFF (2018) 2030 Road Map https://nff.org.au/policies/roadmap/

[21]FIAL (2020) Capturing the prize. https://www.fial.com.au/sharing-knowledge/capturing-the-prize